Camel Up is a deceptively simple board game in which the aim is to predict the outcome of a camel race. I’ll quickly try to explain the game now, although it’s always hard to explain a boardgame without an actual demonstration.

The camel movement is randomly generated from dice rolls as follows. Five dice coloured for each of the five camels, each labelled with the numbers 1-3 twice, are placed into a container (decorated as a pyramid, since the game is set in Egypt), which is then shaken. A dice is drawn from the pyramid with the corresponding camel advancing the number of squares denoted by the face-up dice value.

The game is split into legs, or rounds, with a round ending when all the five dice having been drawn from the pyramid. At each player’s turn, they can choose to either place bets, or move a camel. The bets can either be placed on the leg winner, or the overall winner or loser. At the end of each leg the five dice are placed back into the pyramid and the bets on the leg winner are settled. The race ends when a camel crosses the finish line at 16 tiles, this normally takes around 4 legs.

There is one other mechanic that adds significant complexity to the game, stacking. If two camels are on the same tile, they form a stack, with the camel arriving later being on the top (essentially a First In / First Out stack). When the dice is rolled for the camel on the bottom, they will move themselves and any camel stacked on top of the them by the corresponding amount, meaning there is significant advantage to being on top of a camel stack.

Predicting the winner

One of the reasons why we’ve been enjoying Camel Up is that you can approach it with minimal strategy and just have a laugh (and often do rather well), or you can over think every decision and try to play with an optimal strategy (and generally lose in my experience). I like to try and place educated bets, identifying which camel has the highest probability of winning the leg or the overall race.

However, owing to the stacking mechanism, the order in which the dice

are drawn from the pyramid makes a difference to the outcome. For

example, if you have a stack of [blue, red] camels on tile 3, and you

roll a blue 2 then a red 1, the outcome will be the blue camel on tile

5, and red on tile 6. If you roll the exact same dice values but in the

opposite order, then you end up with the red camel on tile 4, and the

blue camel on tile 5, i.e. the order of the winners has changed.

To predict the outcome of a leg, yet alone the overall winner, is therefore very challenging by analytical means. Since my computing ability is far stronger than my maths, I decided to write a simulation to identify winning probabilities for each of the camels for a given game state. I’m not the first person to use simulation to estimate properties of Camel Up, for example I found this blog post by Greg Stoll where he uses simulation to determine the average number of legs in a game, but I am (as far as I can tell) the first person to use it to estimate winning probabilities for each of the camels. Greg’s simulation does not also incorporate the mechanic of traps that I haven’t discussed yet. These are items that players place on a tile that either move the camel stack forward or backwards by a tile when they land on them.

To get an idea of how complex the game can get, let’s see how many permutations there are from drawing 5 different dice which each have 3 possible values, where the order of the draw is significant. After spending 10 minutes trying to determine it analytically and ending up with a headache, I used simulation.

camel_cols <- c('b', 'y', 'r', 'g', 'w')

dice <- seq(3)

draw_outcome <- function() {

cam_shuff <- sample(camel_cols, 5, replace=F)

paste(sapply(seq(5), function(i) {

paste(cam_shuff[i], sample(dice, 1), sep='')

}), collapse='_')

}

This function outputs as a string a possible series of 5 draws from the pyramid:

draw_outcome()

## [1] "b1_g3_y1_r2_w1"

By repeating this a large number of times (far greater than we’d expect the number of permutations to be) and counting the number of unique orderings we can determine the number of permutations (note that I ran this a few times to check it always output the same number).

outcomes <- replicate(1e6, draw_outcome())

length(unique(outcomes))

## [1] 29160

Yep, with 29,160 possible dice permutations, a simulation approach will be much easier!

R package

I wrote a Monte Carlo simulation to estimate the outcome probabilities

and wrapped it up into an R package that can be found on my GitHub

page. Install the package

with the following command from within RStudio (assuming devtools is

already installed):

devtools::install_github("stulacy/CamelUp-Solver/camelsolve")

The only function that the package provides is called camelsolve,

which estimates the probability of the following 3 outcomes for every

camel:

- Winning the current leg

- Winning the overall race

- Losing the overall race

The documentation (?camelsolve) provides full details how to use the

function; essentially it requires a matrix representing the current

location of the camels and traps, a vector indicating which dice have

already been rolled, and the number of simulations to run (defaults to

1000). As the code is written in Rcpp it is very quick, with a thousand

simulations running instantaneously.

Note that the overall winner/loser probabilities will be slightly inaccurate as they assume that the traps stay on the same tiles between legs, when this is not necessarily the case as they are returned to the players each round. To obtain the most accurate possible results, the function should be run at the start of each leg when the traps have been placed.

Shiny app

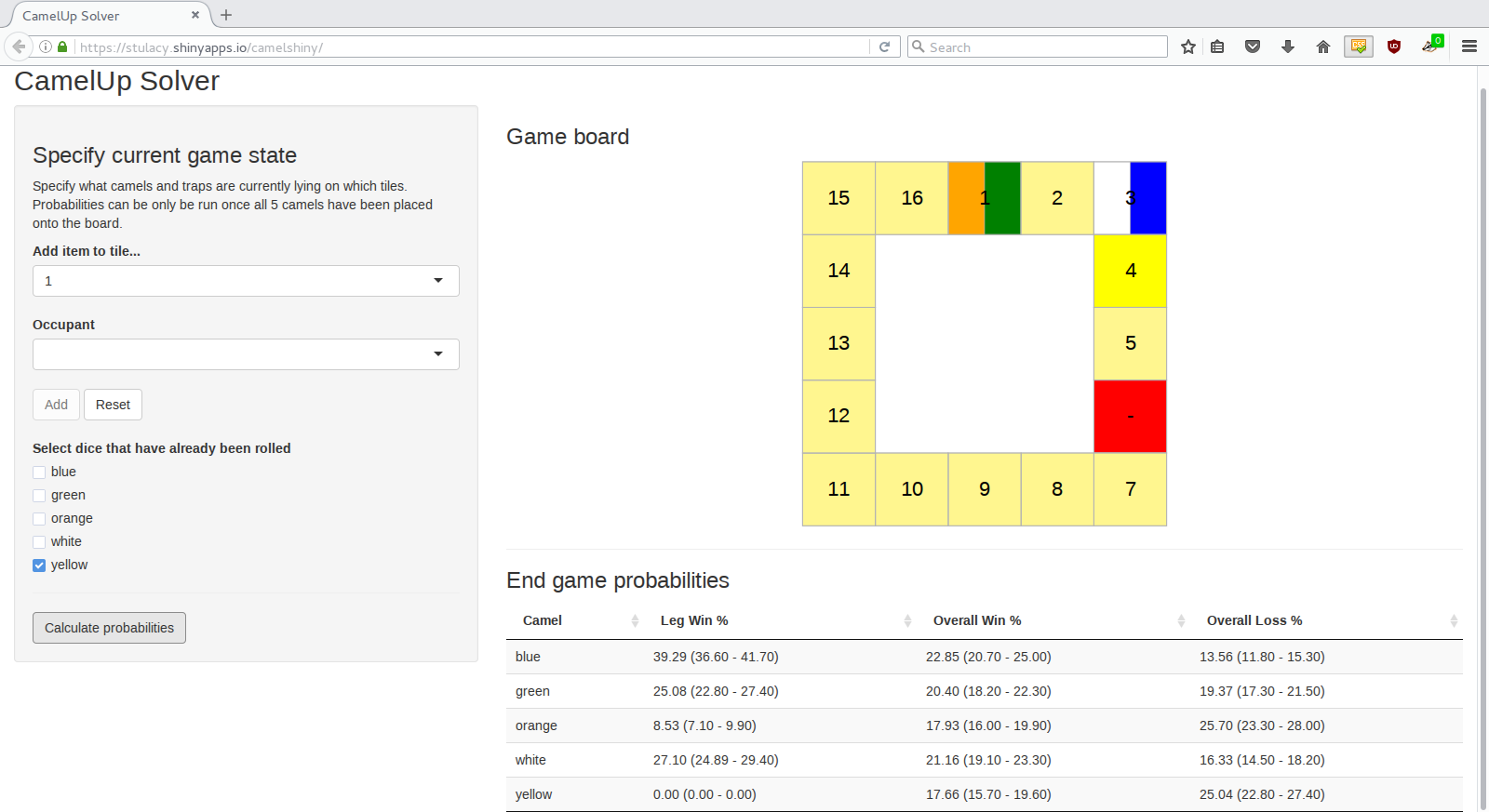

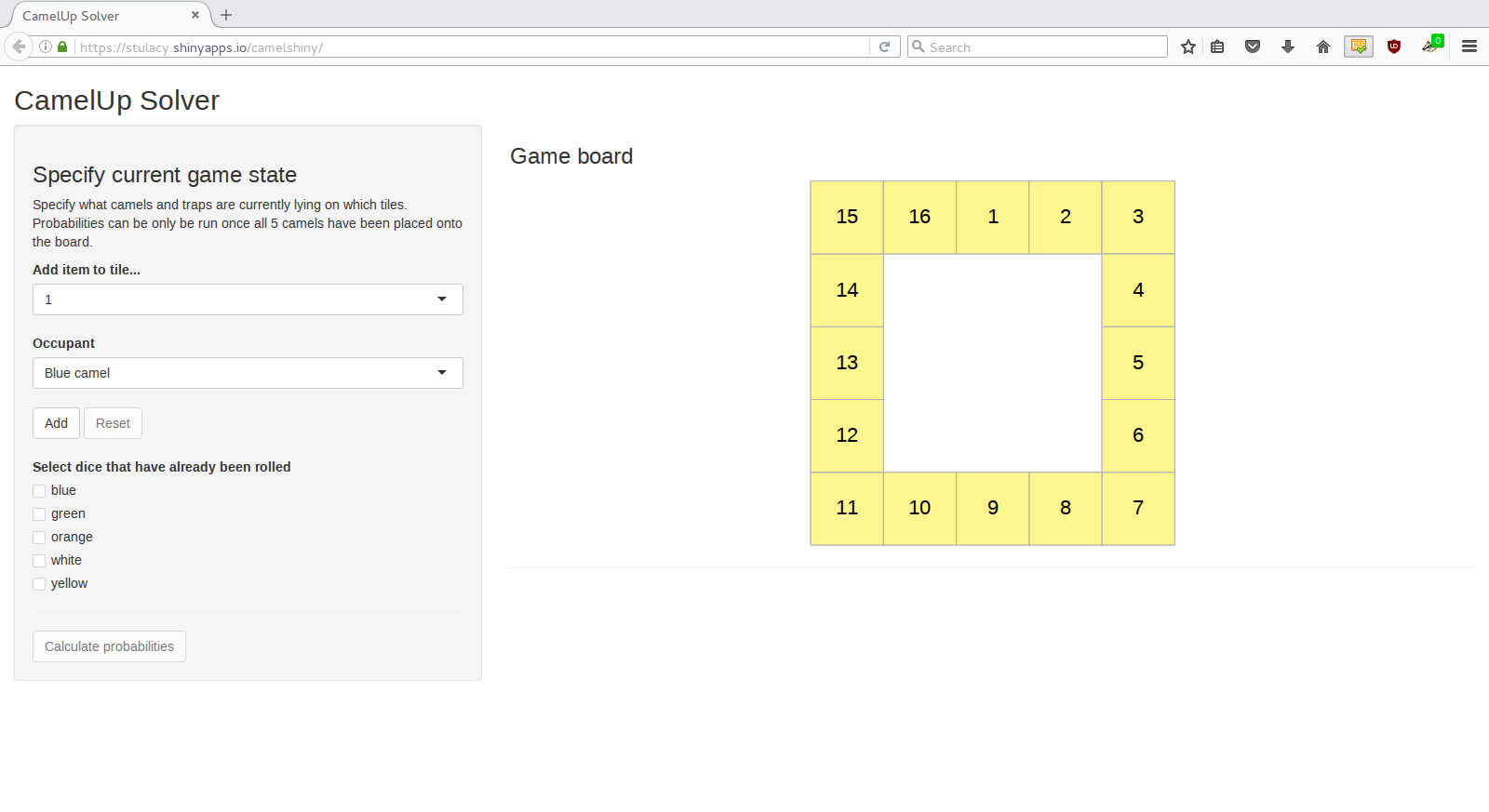

I’ve also made a Shiny web-app front-end for the solver, which can be found here.

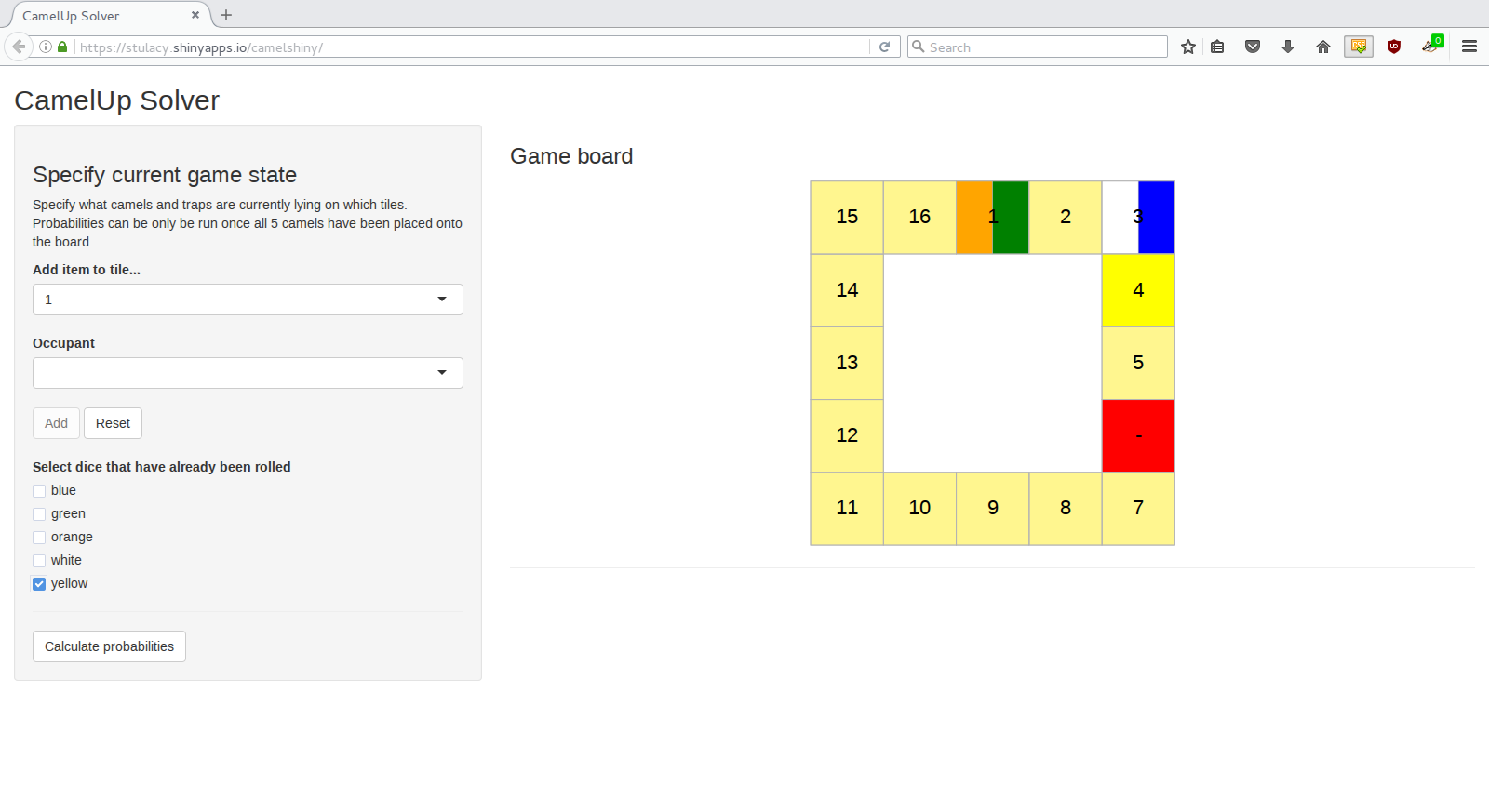

To use it, simply place the camels in their current tiles using the options in the side-bar. Note that you place the camels at the bottom of the stack first, so if you have a stack with Blue at the bottom and Orange on top, add Blue then Orange.

The colour of the tiles represents their occupants, with camels having vertical stripes with the stack order going from left to right. Traps are represented by solid green and red with plus and negative signs for forward and backwards traps respectively.

In the board state pictured below, the green camel is on top of the orange camel on tile 1, the blue camel is on top of the white camel on tile 3, and the yellow camel is alone on tile 4. There is a solitary negative trap on tile 6. The only dice that has been rolled so far is the yellow dice.

The Shiny app does provide one small additional piece of functionality over the R package, in that it repeats the simulations an additional thousand times to obtain 95% prediction intervals for the predicted outcomes. The screenshot below details the output of running the simulation. Unsurprisingly, the blue camel has a very high chance of winning the current leg; despite the yellow camel being ahead on the board it has already rolled its dice and so cannot advance any further. The overall winner column highlights there’s no clear winner yet, with 3 camels having very similar chances. This serves as a reminder to not place bets until sufficient information is available, maybe after 2 complete legs. It is much easier to predict the overall loser, however, with two camels by far the most likely to lose. This coincides with my observations after playing around with the solver, that it is generally far easier to predict who will lose the race owing to the massive disadvantage of being on the bottom of a stack.